Commodity Portfolio Management Series - 1. Refinery Margin Insights: Decoding the Crack Spread

Cracking Open the Concept

What exactly is a crack spread? In the petroleum industry, refinery executives are always keeping a watchful eye on the gap between their input costs and output prices. Their profits are intrinsically linked to this gap, representing the difference between the price of crude oil and the prices of refined products like gasoline and distillates (including diesel and jet fuel).

This differential is what we call a crack spread. The term "crack spread" originates from the refining process itself, where crude oil is 'cracked' into its primary refined products. It's essentially the profit margin a refinery earns from processing crude oil. You'll often hear it mentioned concerning contracts for crude oil, gasoline, and diesel (ULSD), which are subject to regulation by entities such as NYMEX, a CME Group exchange.

Caught in the Middle

A petroleum refiner operates in a unique predicament, sandwiched between two markets: procuring raw materials and offering finished products. The prices of crude oil and its refined products are influenced by independent factors like supply, demand, production economics, environmental regulations, and more. This positioning can expose refiners and non-integrated marketers to significant risks, especially when crude oil prices surge while refined product prices remain stable or decrease. This scenario also dramatically narrows the crack spread, eroding the profit margin a refiner gains when purchasing crude oil while concurrently selling refined products in a competitive market. As they straddle both sides of the market, refiners face greater market risk compared to companies that deal exclusively with crude oil or sell products to wholesale and retail markets.

Aside from covering the operational and fixed costs of running a refinery, refiners aim for a return on their investments. They can generally predict their costs, except for crude oil, making an unpredictable crack spread a major financial concern. Furthermore, investors might use crack spread trades as a hedge against a refining company's equity value. Professional traders could also consider crack spreads as a directional trade in their energy portfolio due to their low margins, which receive a substantial spread credit for margining purposes. Together with indicators like crude oil inventories and refinery utilization rates, changes in crack spreads or refining margins offer insights into where certain companies and the oil market might be heading in the near term.

Hedging the Crack Spread

To manage the price risk associated with operating a refinery, various crack spreads come into play. These spreads help refiners hedge different ratios of crude and refined products based on their plant configuration, crude slate, and seasonal market demands.

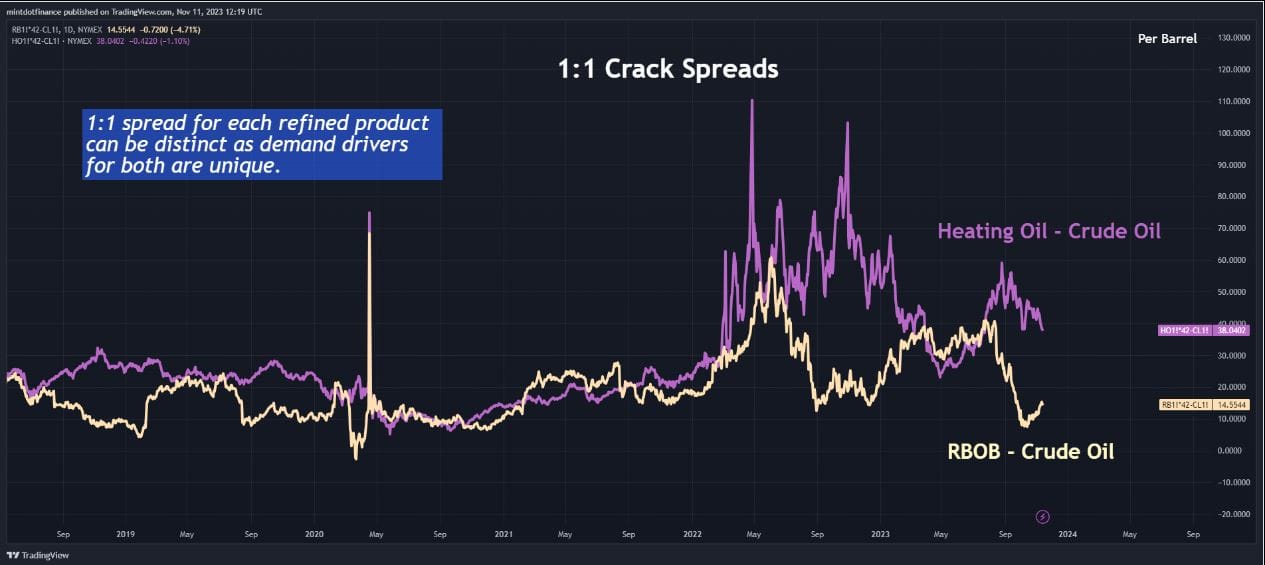

- Simple 1:1 Crack Spread: The most common crack spread is the simple 1:1 crack spread, representing the profit margin between refined products (gasoline or diesel) and crude oil. This spread is executed by selling/buying refined product futures (gasoline or diesel) and buying/selling crude oil futures, effectively locking in the difference between refined products and crude oil prices.The crack spread is quoted in dollars per barrel, requiring the conversion of cents per gallon prices for refined products to dollars per barrel (using the fact that there are 42 gallons in a barrel). If refined product prices exceed crude oil prices, the cracking margin is positive; otherwise, it's negative.When refiners anticipate stable or rising crude oil prices alongside falling product prices, they may "sell" the crack by selling gasoline or diesel futures and buying crude oil futures.However, at times, refiners might do the opposite: buying refined products and selling crude oil, effectively "buying" a crack spread to protect against increasing product prices and decreasing crude oil prices. This spread helps traders to express their view on the relationship between single type of refined product against crude oil. It is useful when price of one of the refined products diverges from crude oil prices.

1:1 spread is deemed useful when there are distinct conditions affecting each of the refined products.

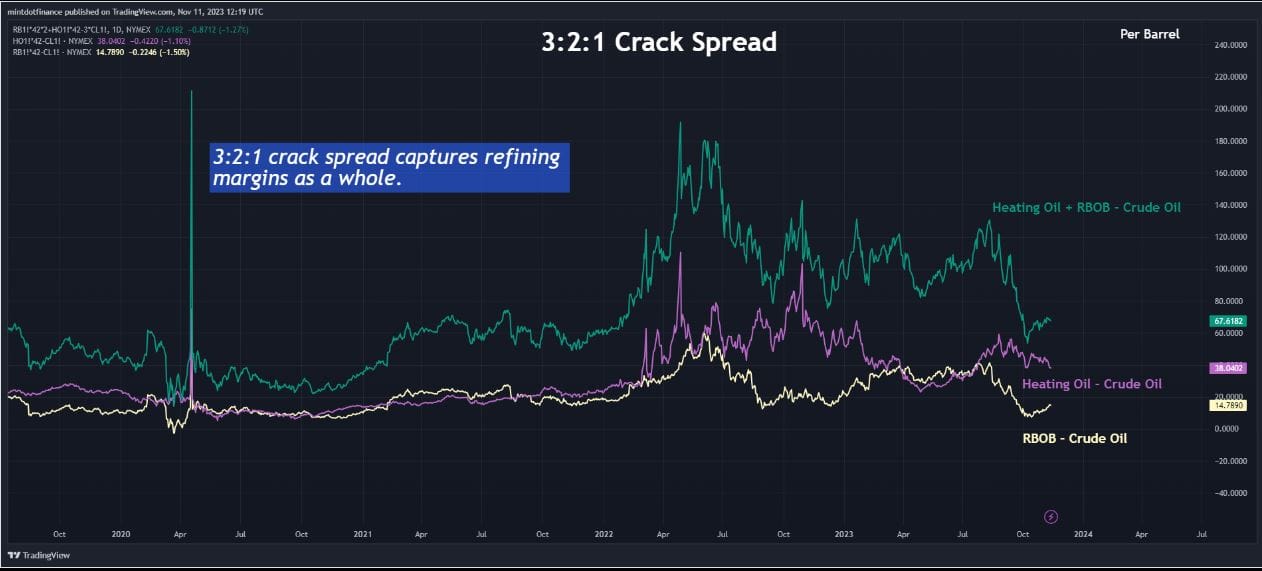

Diversified 3:2:1 and 5:3:2 Crack Spreads: More complex crack spread strategies aim to replicate a refiner's yield of refined products. In a typical refinery, gasoline output is usually about twice that of distillate fuel oil. This 3:2:1 crack spread involves three crude oil futures contracts, two gasoline futures contracts, and one ULSD diesel futures contract. For instance - (3 contracts of CL) on one leg and (2 contracts RBOB + 1 contract of ULSD) on the other leg. The entire position thus consists of six contracts. It assumes that three barrels of crude can be used to create two barrels of RBOB and one barrel of Heating oil (HO).

This trade is better at capturing the actual refining margin. It is commonly used by refiners to hedge their market exposure to crude and refined products. 3:2:1 spread is commonly used by investors to express views on conditions affecting refineries.

- Refiners with different yield ratios may opt for alternative crack spread combinations, such as the 5:3:2 crack spread. This ratio requires selling five refined product futures (three RBOB gasoline futures and two ULSD futures) and buying five crude oil futures contracts; For instance - (5 contracts of CL) on one leg and (3 contracts of RBOB + 2 contracts of heating oil) on the other leg, closely mimicking the refiner's cracking margins, and capturing the actual proportions from the refining process. Professional traders may also utilize diversified crack spreads as part of their portfolio for directional trading, and hedge funds could use these spreads as a safeguard against a refining company's equity value. However, this spread is also more capital-intensive.

When to Apply a Crack Spread

Crack spreads are more than just an industry concept; they represent the fine line between profit and loss for refiners. This method provide a way for refiners to navigate the volatile waters of the petroleum market, offering a means to manage risk and protect their bottom line.

Determining when to apply a crack spread involves careful analysis of market conditions. A refiner typically uses crack spreads when they anticipate changes in the relative prices of crude oil and refined products. For instance, if they expect crude oil prices to remain steady or rise while product prices decline, they may consider applying a crack spread to hedge against a narrowing profit margin.

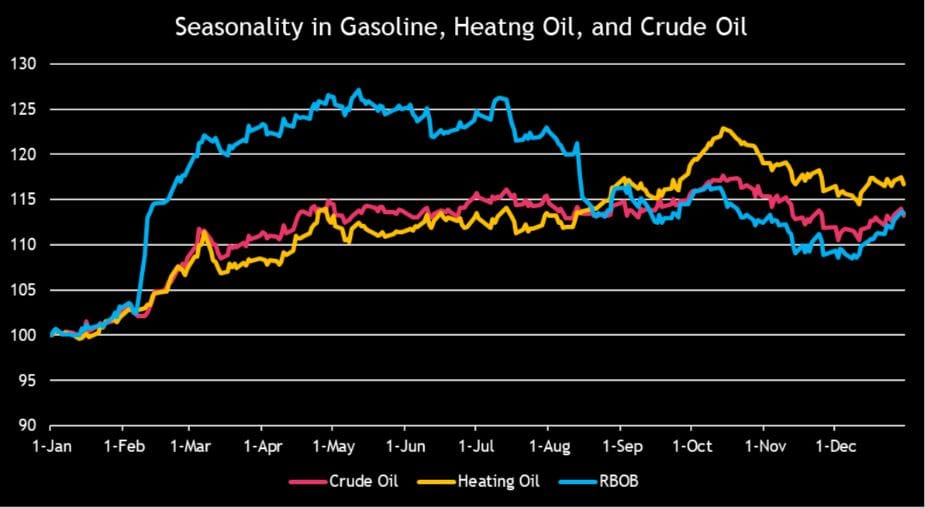

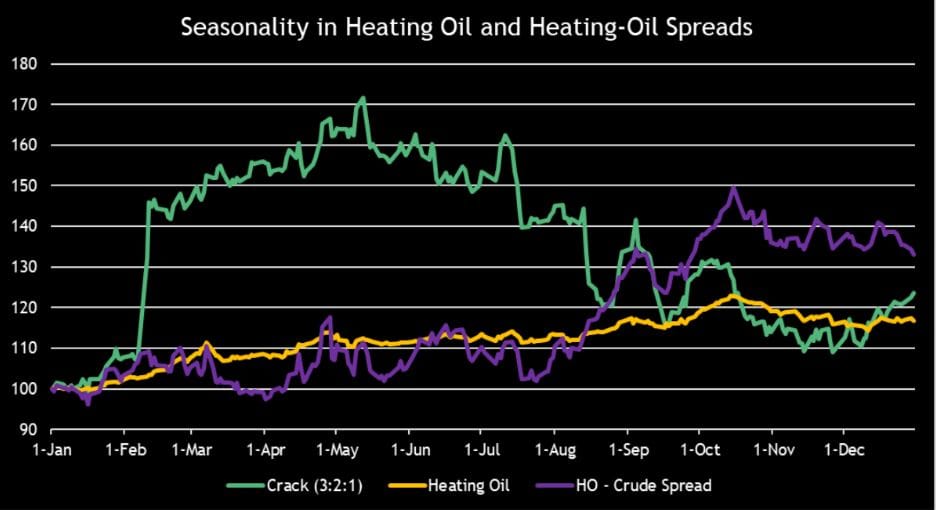

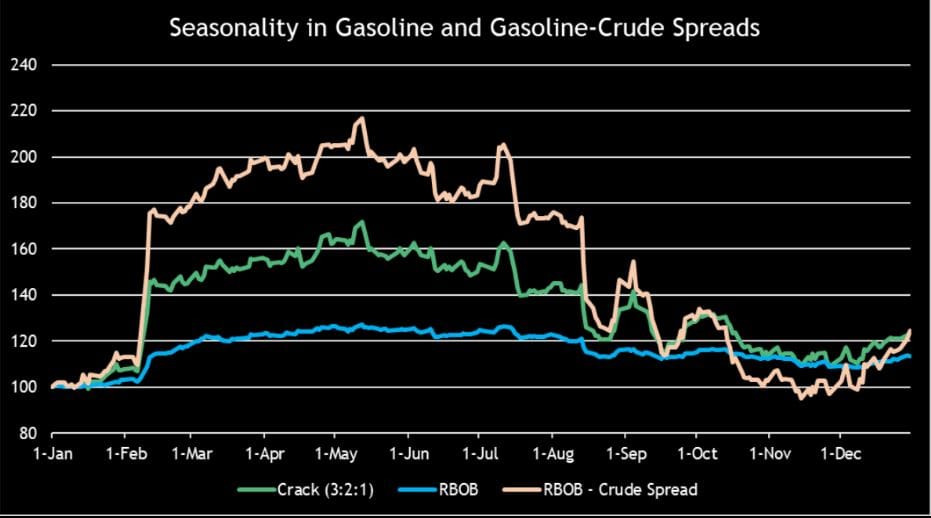

Seasonality, supply-demand dynamics, and inventory levels collectively impact crack spreads. We will cover these factors that affects crude oil prices in a separate article. For seasonality in short, crude seasonality is influenced by variation in refined products demand. Gasoline demand tends to be higher during summer. Conversely in the winter, distillate demand is higher. As such, seasonal price performance of the three contracts is distinct leading to a unique seasonal variation in various crack spreads. Summary performance of the three spreads is provided below.

Left: Heating Oil to Crude spread seasonality ; Right: Gasoline to Crude spread seasonality

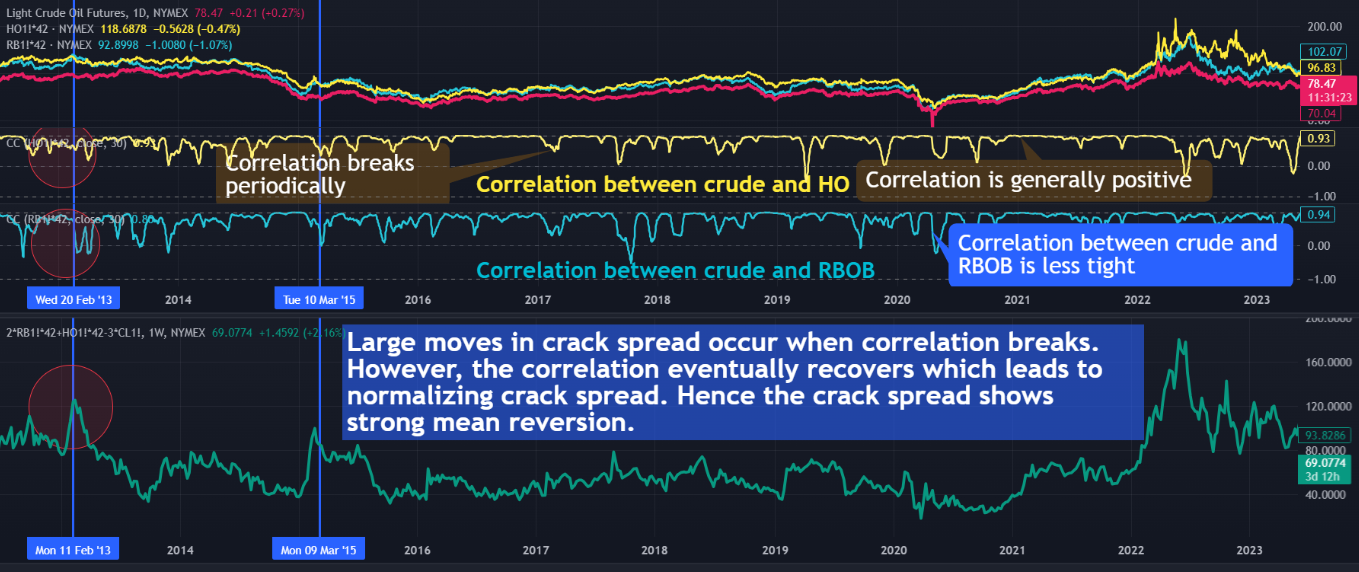

Supply and inventories of crude oil and refined products also influence crack spreads. When inventories of refined products remain elevated, their prices decline narrowing the spread. This happens in a case when refiners ramping up refinery capacity ahead of peak demand in summer and winter, building up inventories to meet anticipated high demand. As the spread reaches its lowest point, refiners take capacity offline for maintenance. In contrast, when the production and inventory of crude oil is elevated, crack margins begin to expand as refined product supplies dwindle, aligning with decreased crude oil consumption. This results in a gradually increasing spread through high consumption periods. For demand, Refinery demand has a self-balancing effect as higher refining requires higher consumption of crude which acts to increase crude oil prices. Demand for crude oil and refined products is broadly correlated. However, there are often periods when demand diverges on a short-term scale. Demand for refined products can also precede or lag demand for crude oil from seasonal as well as trend-based factors. This lag can be identified using the crack spread. Sharp moves in crack spread pre-empt moves in the underlying which act to normalize the spread as shown below.

Which to sum up:

i) When inventories of refined products remain elevated, their prices decline narrowing the spread. Investors can position short on the crack spread in anticipation of ample supply. Conversely, if refined product inventories are low, investors can position long on the crack spread.

ii) When the production and inventory of crude oil is elevated, its price declines leading to a widening spread.

iii) On the contrary, low inventories of refined products can lead to a wider crack spread and low inventories of crude oil leads to a narrower crack spread. When inventories of crude are stable or elevated, it indicates less demand from refiners. Investors can opt to position long on the crack spread anticipating ample crude supply.

Prices of refined products have been affected more negatively by low demand than crude oil. Inventories and supply situation for refined products is more secure than crude oil. Still, seasonal trends suggest an expansion in crack spread once refined product inventories start to be depleted.

Choosing the Right Type of Crack Spread

The choice of the appropriate crack spread depends on a refiner's specific circumstances. For example, a refiner focused on gasoline production might prefer a 3:2:1 crack spread, which aligns with their product yield. On the other hand, a refiner with a different yield ratio, such as a higher output of distillate fuel oil, might opt for a 5:3:2 crack spread.

As a case study - imagine a sharp decline in crack spread which is likely to revert, and seasonal trend pointing to increase in the crack spread, investors can take a long position in the crack spread. This consists of:

• Long position in 2 x RBF2024 and 1 x HOF2024

• Short position in 3 x CLF2024

The position profits when:

1) Price of RBOB and ULSD rise faster than Crude.

2) Price of Crude declines faster than RBOB and ULSD.

The position looses when:

1) Price of Crude rises faster than RBOB and ULSD.

2) Price of RBOB and ULSD declines faster than Crude.

Alternatively, if there is relative bullishness in distillate inventories plus stronger seasonal demand for distillates during winter, margins for refining heating oil will likely rise faster than gasoline refining margins. Focusing the expanding crack margin on a 1:1 heating oil margin spread can lead to a stronger payoff.

This position consists of Long 1 x HOF2024 and Short 1 x CLF2024.

The position profits when:

1) Price of ULSD rises faster than Crude.

2) Price of Crude declines faster than ULSD.

The position will endure losses when:

1) Price of Crude rises faster than ULSD.

2) Price of ULSD declines faster than Crude.

Alternatives to Crack Spread

There are alternatives to crack spreads. Common methods include Arbitrage Spreads which are oil prices in one region minus prices for a similar grade of oil in another region, and are a function of transportation rates between regions. For example, diesel in Rotterdam vs Venezuela. Common examples of arbs traded in the oil market includes the TI-Brent Crude Oil arb (Atlantic Arb). Conversely, Spreads that are applied to similar products but the same region are known as Relative Value Spreads. For instance, a type of relative value spread is known as a regrade, which is the relative value spread between different grades of gasoline in the US, or between kerosene and gasoil in Asia. And on top of these spreads, traders can place a time varying element in their spreads when dealing with seasonality, by taking differences between the prices of the commodity in one time period vs the price of another time period. Its worth noting that time spreads can be a combination of crack, relative value and arbitrage spreads at the same - for example - a box spread.

In conclusion, crack spreads are a vital tool in the world of commodity portfolio management, offering opportunities for both refiners and traders to optimize their financial positions.

- Crack spread refers to the gross processing margin of refining (“cracking”) crude oil into its by-products.

- Refined products RBOB and ULSD can be traded on the CME as separate commodities. Both are representative of demand for crude oil from distinct sources.

- Crack spreads are affected by seasonality, supply, and inventory levels of crude and refined products, as well as demand for each refined product.

- A low-demand outlook for refined products of crude is prevalent due to expectations of an economic slowdown.

- There are three types of crack spread: 1:1, 3:2:1, and 5:3:2.

a. 1:1 can be used to express views on the relationship between one of the refined products and crude.

b. 3:2:1 can be used to express views on the refining margin of refineries.

c. 5:4:3 can give a more granular view of proportions of refined products produced at refineries but is far more capital-intensive.

As the energy industry continues to evolve, understanding the dynamics of crack spreads will remain essential for anyone looking to make informed decisions in this complex marketplace. Whether you're a refiner securing profit margins or a trader seeking strategic positions, crack spreads are a fundamental aspect of the industry's financial landscape.